John Martinkus 1969-2025

The last thing photographer Richard Downie expected when he accompanied tenacious journalist John Martinkus to Dili last year to cover the visit of Pope Francis to Timor-Leste was for President Jose Ramos Horta to clamp a hand on his shoulder, fix him with a steely gaze and tell him: “Look after John. He is a very great man. To me. And to Timor-Leste.”

“You start to realise your mate may not be as full of shit as you thought,” Downie reflected this week.

Journalist and lawyer Mark Davis made a similar comment on Radio National: “What was incredible, when I was in Timor with John, was this groundswell of love from the people there, he really was a big deal in East Timor. Deservedly so.

“You don’t get many big wins in journalism, not many guys can say they helped to create a nation. John certainly did.”

John Martinkus, who died on 15 September at age 56, was an irascible, passionate, and often pugilistic interrogator of the truth in unfailingly the most inhospitable of places.

Last year, Ramos Horta presented him with the Order of Timor-Leste for “his contribution to the benefit of the country, the Timorese, and humanity.” This week he paid tribute again, calling Martinkus: “One of the bravest journalists ever.”

Sadly, there have been no similar words of tribute from Australian political leaders, past or present.

Truly, he was the last of the independents, “freelance” to the point of outsider. Martinkus had managed to slip into Indonesian-occupied East Timor in 1995 when the world wasn’t interested and countries like Australia were still in denial about what was happening in the former Portuguese colony.

This was a constant source of anger and frustration to him in those years. Nevertheless, he was the first to report on the build-up of the Indonesian-backed militia, which were determined to keep Timor as the subjugated 27th province in a post-Suharto Indonesia.

“Around 1998, before the referendum [for independence] was even in sight, John was filing these tiny articles, 200-worders, that were published in places like Western Australia, about the situation,” says Davis. “They were his best words, most significant words, but least [amount-wise] words.”

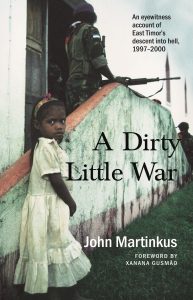

John Martinkus was born in Melbourne in 1969, the youngest child of a Lithuanian migrant father and Australian mother. He studied international relations at LaTrobe and learned Russian in Moscow. It wasn’t until he visited Timor-Leste that he began to seriously take up journalism, freelancing for the Associated Press and various Australian mastheads. His experiences in the lead-up to, and aftermath of, the UN-sponsored referendum for independence in 1999 resulted in the book A Dirty Little War.

Later, he reported for SBS Dateline from the Middle East and Iraq, and was commissioned as Official Cinematographer for the Australian War Memorial in Afghanistan. He also taught in the University of Tasmania’s School of Journalism, Media and Communications.

Detachment was not part of the Martinkus style. He took injustice, ignorance, and brutality against the weak personally and would get incandescent with rage and indignation when anyone – especially editors and other colleagues – failed to register the same level of compassionate outrage.

In this way he was perhaps a romantic, in the way American journalist John Reed took a partisan-approach to reporting the Russian Revolution. And, like Reed, Martinkus often came under fire for being subjective and too starry-eyed about freedom fighters.

In October 2004, after being detained for 24 hours by armed Sunni Muslims in Baghdad, Martinkus said: “These guys, they’re not stupid … There was a reason for them to kill [British hostage Kenneth] Bigley, there was a reason to kill the [two] Americans. There was no reason to kill me.”

Then-Foreign Affairs Minister Alexander Downer said: “It’s pretty close to the most appalling thing any Australian has said about the situation in Iraq.”

Former aid worker Steve Pratt, himself held hostage in Yugoslavia for five months in 1999, said Martinkus’ remarks were “arrogant” and that he was “making excuses for executioners”.

When asked how he survived his ordeal and kept his captors engaged, Martinkus offered: “I just kept talking.”

This, friends and former colleagues could well believe: that outraged, cigarette-growl as he held forth on matters he deemed unjust and immoral.

Three-time Walkley winner and former Age foreign correspondent Lindsay Murdoch: “Although he often seemed gruff and angry, I think beneath all that was a passionate man who cared deeply about injustices, of which he saw many.”

Deakin University emeritus professor Damien Kingsbury adds: “With John’s passing, we have lost a fearless voice.”

Veterans of the Timorese resistance to Indonesian occupation will never forget him. Says “simple clandestine” operator “Pedro”: “John was so engaged in the situation and kept coming although he knew he was under surveillance and in danger. I remember in 1997 when he took a British doctor into the bush to find the guerrilla fighters and treat Commander Alex David’s wounds. John was extraordinary.”

Dr Peter Job, author of A Narrative of Denial: Australia and the Indonesian Invasion of East Timor, says Martinkus insisted on truth-telling while those “masquerading as ‘responsible’ journalists repeated Indonesian and Australian propaganda points, reiterating false narratives about the origin and nature of the conflict and the Timorese genocide”.

British writer Richard Lloyd Parry makes the comment: “You’d have to go back to the Elizabethan pamphleteers to find the equal of his withering indignation.

“Injustice is never in short supply, but few people have sought it out with such determination or documented it so assiduously as John … He had no pomposity, no pretention, and an abundance of the kind of dark, unsentimental humor that often masks warmth and kindness.”

Retired foreign correspondent and editor Ian Timberlake: “You cannot do good journalism without passion. John overflowed with it. Yet he was not a braggart about what he had done.”

And keep talking John Martinkus did. After Timorese independence, he filed seething reports from Indonesian-held Aceh and West Papua. Even in his final years, with limited mobility, he unleashed ardent tirades online. Anything in the news was fair game.

About anti-immigration rallies: “Nazis should be jailed” and, more cuttingly: “Let’s face it. Australia is racist and always has been. Admit it and get over it.”

About the use of discarded rolling-stock for the homeless: “Here is an idea. We have yards of these in Melbourne alone. And lots of people to fill them.”

He sympathised with the Press in Gaza: “Not much else to say except they are being deliberately targeted.”

And on his own capacity for declaiming: “Apparently, according to a family member, I am not allowed to talk about the war. It upsets them. Problem is, I don’t know which war they are talking about.”

Finally, and sweetly, this, on 16 August: “Had a good, strange moment down the pub tonight. I went in to have my usual pint and sat down in the smoking area. A guy I know quite well was sitting there with his mate.

“We started talking as usual and he pulled out of his pocket a copy of the first book I wrote. I couldn’t believe it. It is really hard to find, out of print, and he had a brand new copy. I was so flattered. He hands it to me, wants me to sign it.

“I was like, What do I say? So I wrote something like: ‘This thing damn near killed me to write’ – which it did. He was happy. I was happy. Life is ok.”

John Martinkus leaves behind daughters Lilya, Cara, and Signe, three siblings, nephews and nieces.